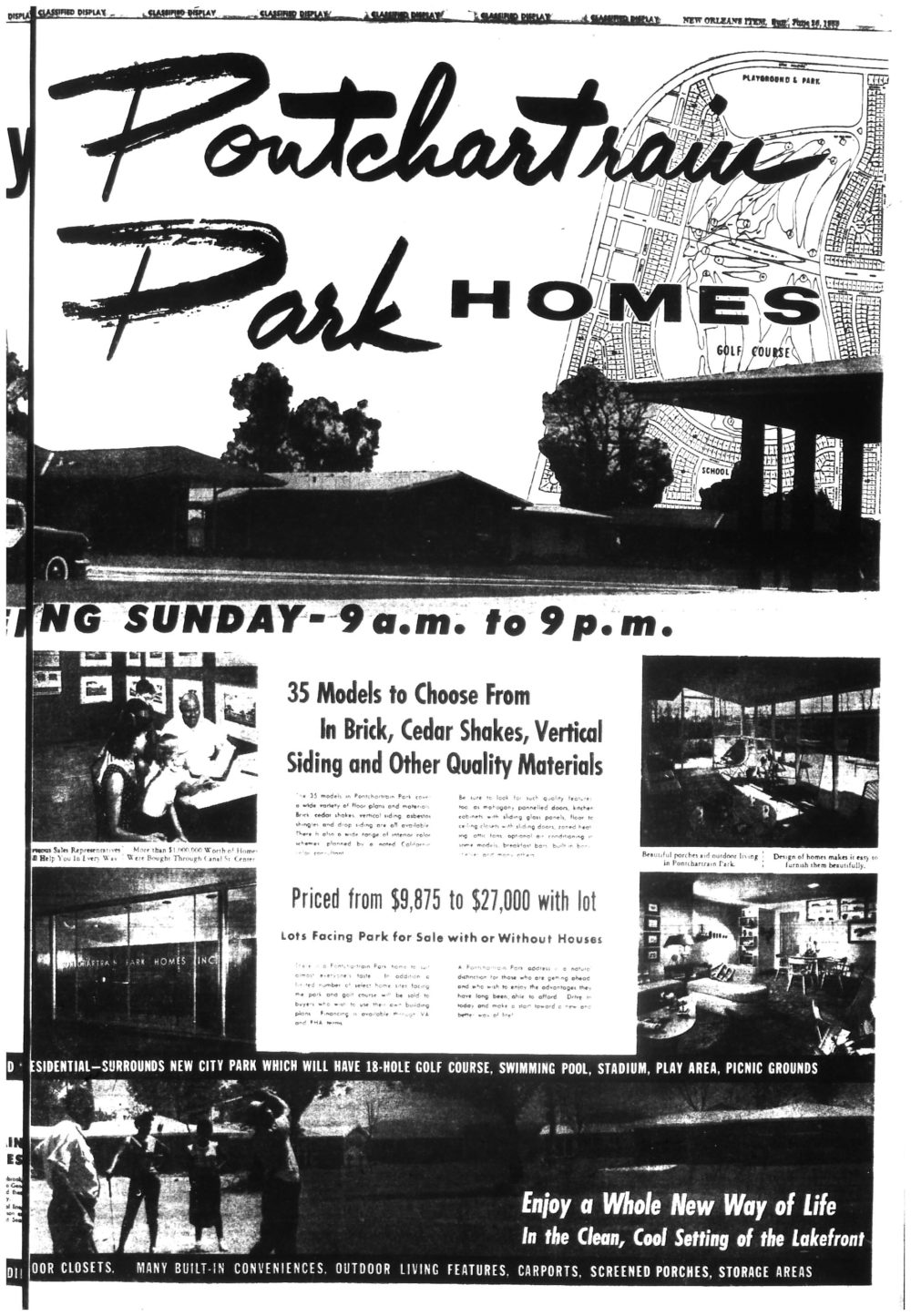

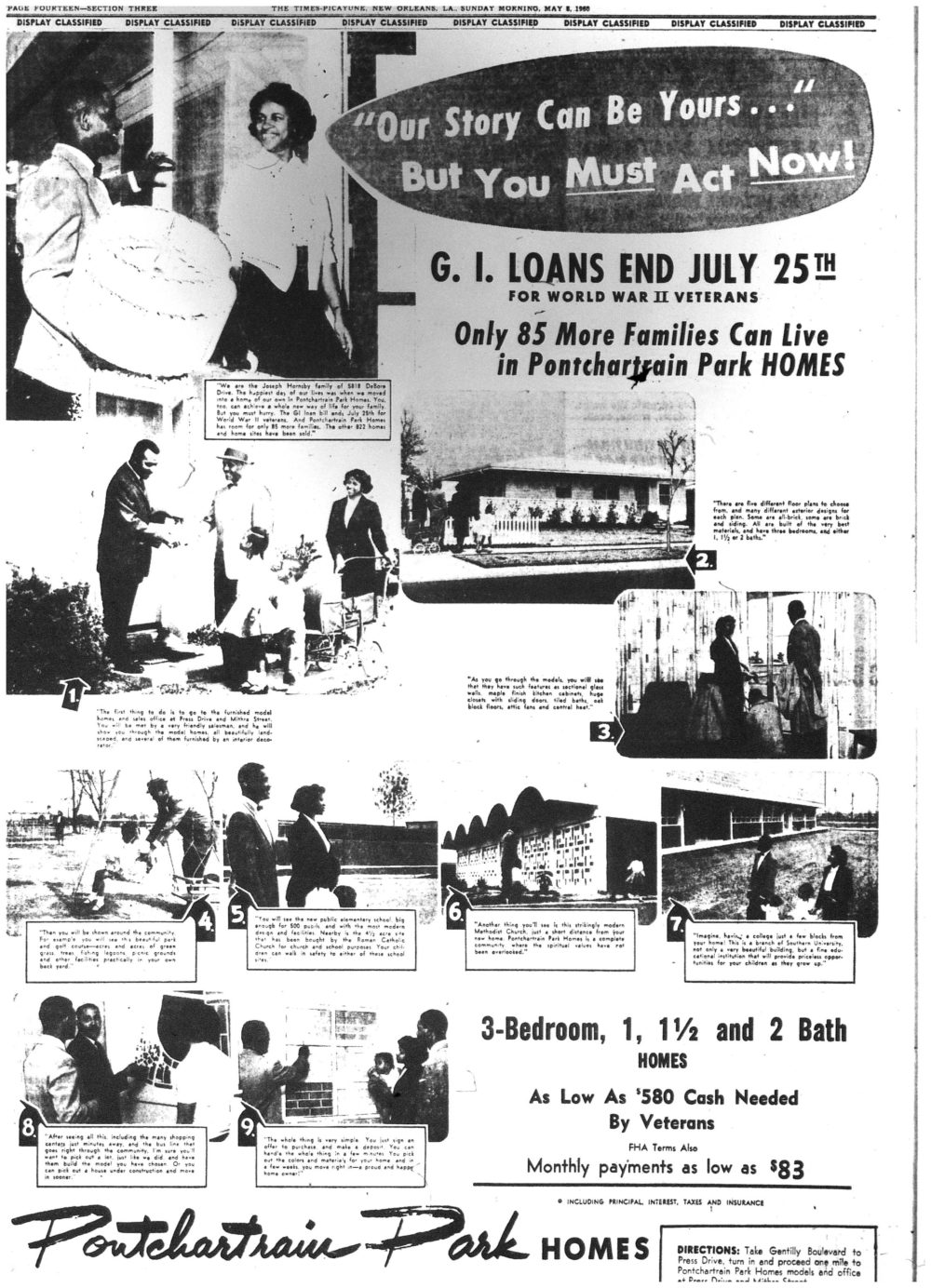

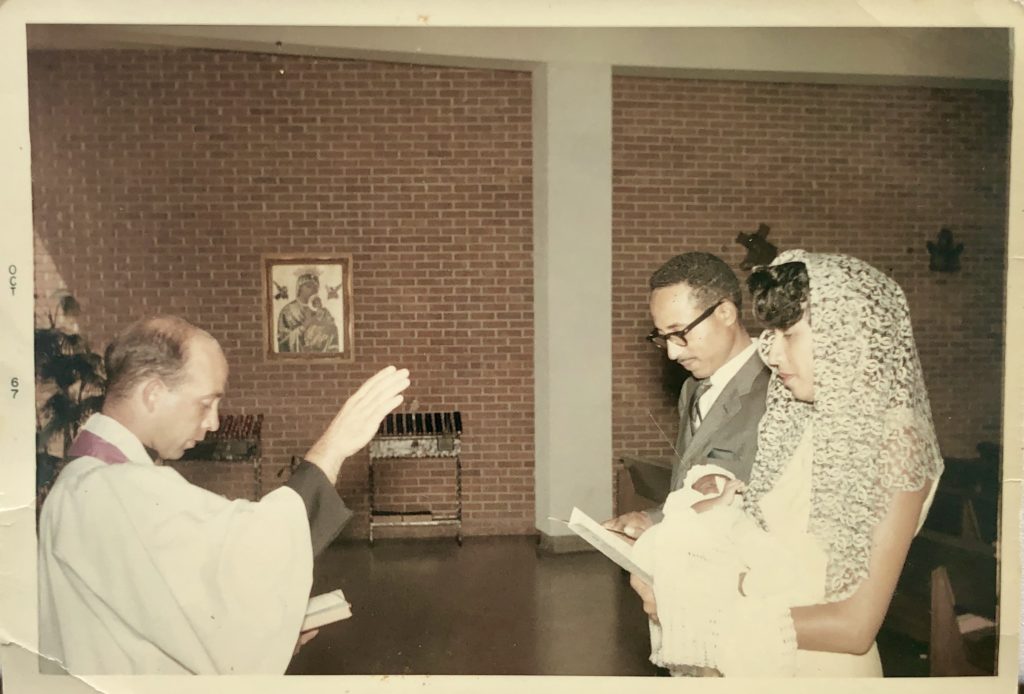

Pontchartrain Park, built between 1955 and 1961, was one of the first suburban-style subdivisions developed for African Americans in the segregated South. Located in the Gentilly neighborhood, where many affluent white residents were moving at the time, Pontchartrain Park attracted middle- and upper-class African-American residents and became a symbol that the American Dream could be a reality for all Americans.

“ONCE-DIVERSE CITY IS NOW SEGREGATED”

– The Times-Picayune

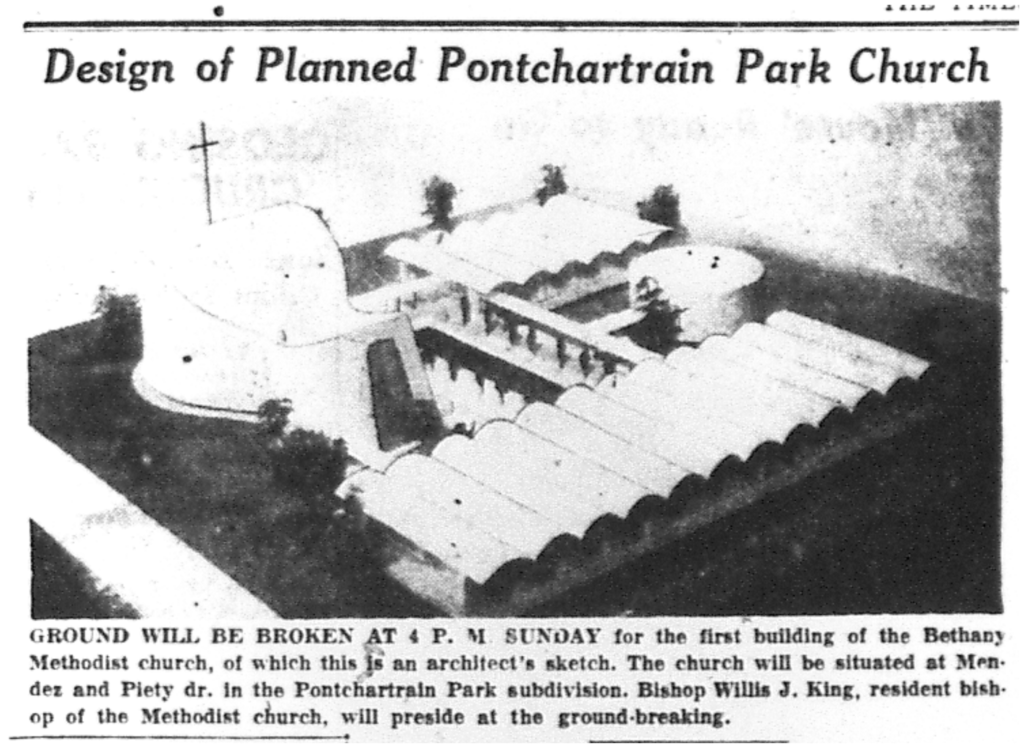

Although Pontchartrain Park opened in 1955, one year after the Brown v. Board of Education case laid the groundwork to dismantle legal segregation in the United States, racial segregation remained legal throughout Louisiana. Years of legislation, lending practices and land-use decisions played a substantial role in reinforcing segregation as the norm throughout the city. The public park at the heart of the neighborhood was developed to serve African-American residents citywide. This was a chief motivator for Mayor deLesseps “Chep” Morrison, who faced criticism that New Orleans failed to provide separate but equal recreation facilities for people of color.

“My parents’ generation took something ugly like segregation and turned it into … one of the most stable American neighborhoods, not only in this city, but around the country”

Wendell Pierce, speaking on CNN, “New Orleans Suburb Rises from Katrina’s Shadow,” Aug. 22, 2010

Beginning with the creation of the Federal Housing Administration in 1934, federally backed mortgage credit was subject to discriminatory policy, denying African-American residents access to homeownership opportunities in both historic neighborhoods and new suburban communities. Using maps created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in the 1930s, commonly referred to as “redlining maps,” loans were denied in any neighborhood where African Americans lived. In spite of this — and over the objection of the NAACP — in 1954, Mayor deLesseps “Chep” Morrison “pleaded with the FHA to insure a subdivision for middle-class black professionals in Pontchartrain Park on a promise that it would not be integrated.”

Gentilly Woods

Pontchartrain Park was designed in the image of Gentilly Woods, a neighboring community by the same homebuilder that opened in 1951 for white residents.

In 1953, the neighborhood association for Gentilly Woods presented a petition with 1,000 signatures against the development of Pontchartrain Park. “Most of the persons who bought homes in Gentilly Woods came from other parts of the city and many from other parts of the country and were not informed when they purchased their property of any proposed Negro development immediately north of Gentilly Woods,” said Ralph Lichtlus, president of the Gentilly Woods Improvement Association. — The Times-Picayune, Nov. 25, 1953.

Southern University at New Orleans

The establishment of segregated neighborhoods and institutions for African Americans was controversial. Accessibility was lauded by many, but the NAACP and others criticized the existence of separate white and black facilities. The United Clubs, Inc., submitted a petition filled with “thousands of signatures” to Gov. Earl K. Long in opposition to the creation of Southern University at New Orleans. The university was proposed to provide higher education opportunities for black students. “The club and petitioners are by no means opposed to the promotion of facilities for higher education in the state of Louisiana and the tremendous need for this and more educational facilities is recognized,” said Raymond B. Floyd, vice president of The United Clubs, Inc., “but we are diametrically opposed to the use of state funds to build a segregated institution at a time when the entire world has voiced its objection to the denial of the rights of the individual.”

High Style Suburban Design

Community by Design

With winding residential streets surrounding a new golf course and sports fields, Pontchartrain Park exemplified a popular 20th-century practice of planning automobile-centric communities that were verdant, pedestrian-friendly and encouraging to neighborly interaction. Based on the Garden City concept popularized by urban designer Ebenezer Howard in the late 19th century, this approach is seen in other noteworthy planned communities, such as Lake Vista in New Orleans. The Park’s success inspired the design of the Beau Chene neighborhood in Mandeville. “When I did Pontchartrain Park, I realized for the first time the feeling of spaciousness you get when you build around a golf course, so we wanted to incorporate that into Beau Chene,” recalled Morgan Earnest, executive vice president of Pontchartrain Park Homes, Inc., and co-developer of Beau Chene in Mandeville. — The Times-Picayune, Jan. 8, 1984

Restrictive Covenants

While restrictive covenants were used in many subdivisions to restrict homeownership by African Americans and reinforce patterns of segregation, such rules also helped establish the neighborhood character and quality of life that defined Pontchartrain Park. For example, the expansive front yards in the neighborhood were protected in the Pontchartrain Park Restrictive Covenant regulations concerning fences.

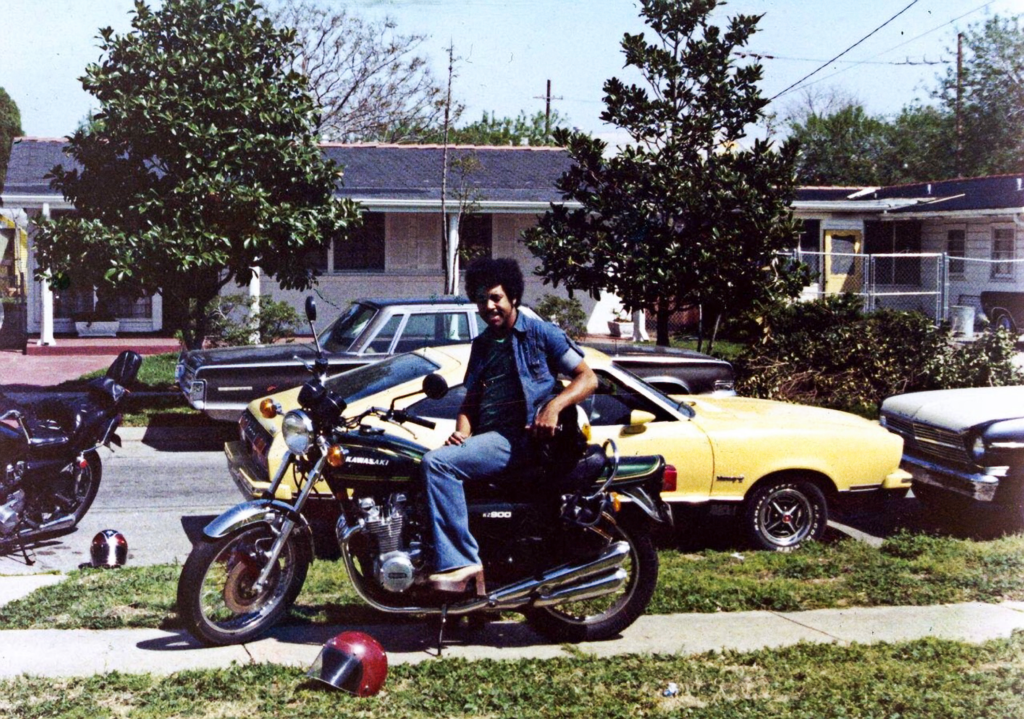

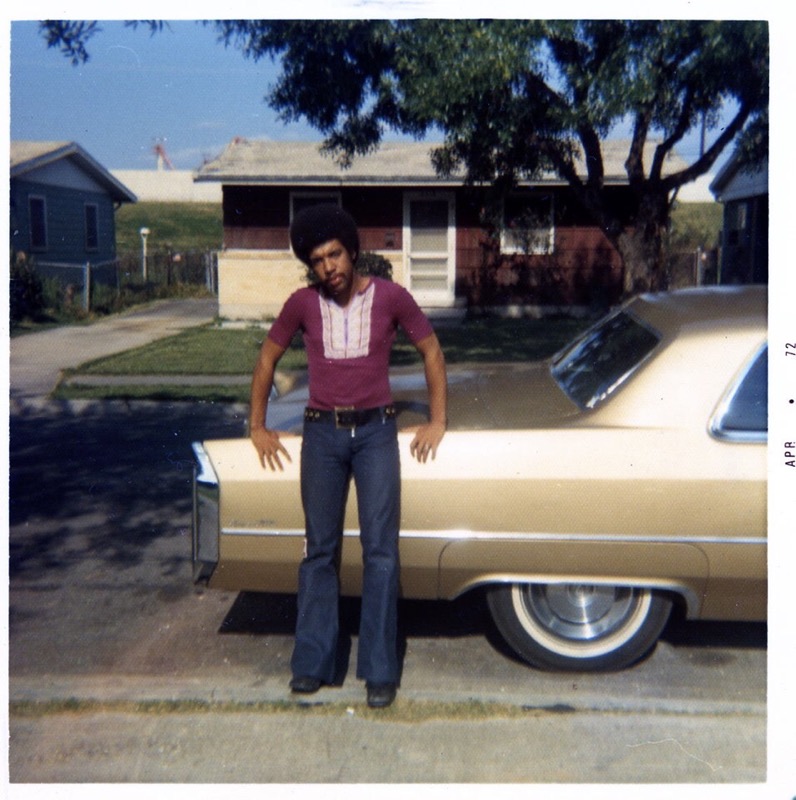

Technology Influences Architecture

The majority of the homes in Pontchartrain Park were two- or three-bedroom ranch-style houses, set back from the street and sidewalk by front yards and flanked by carports. The construction of these homes atop concrete slabs, particularly in this former cypress swamp, was enabled by earth-moving and drainage technology. The advent of air conditioning for residences also influenced the design, as open windows were no longer the only means to counter warm Southern summers. The ranch house used the tools and technology available after World War II to reimagine the New Orleans family home.

1 – Homes were built atop concrete slabs because of earth-moving and drainage technology.

2 – These mid-century modern homes were ideal for growing single-families. Often, residents would add onto the original structures, enclosing carports or adding a second story.

3 – Carports were an essential feature of the homes in Pontchartrain Park. The planned community was designed around families whose primary mode of transportation was a shared vehicle.

4 – The advent of air conditioning for private homes also influenced fenestration because open windows were no longer the only means to counter New Orleans’ famously hot summers.

5 – Brick veneers were commonly applied to the façade of the homes.

6 – Mid-century modern style homes favored low rooflines. In rainy New Orleans, mid-century homes pitched their roofs in lieu of a flatter silhouette.

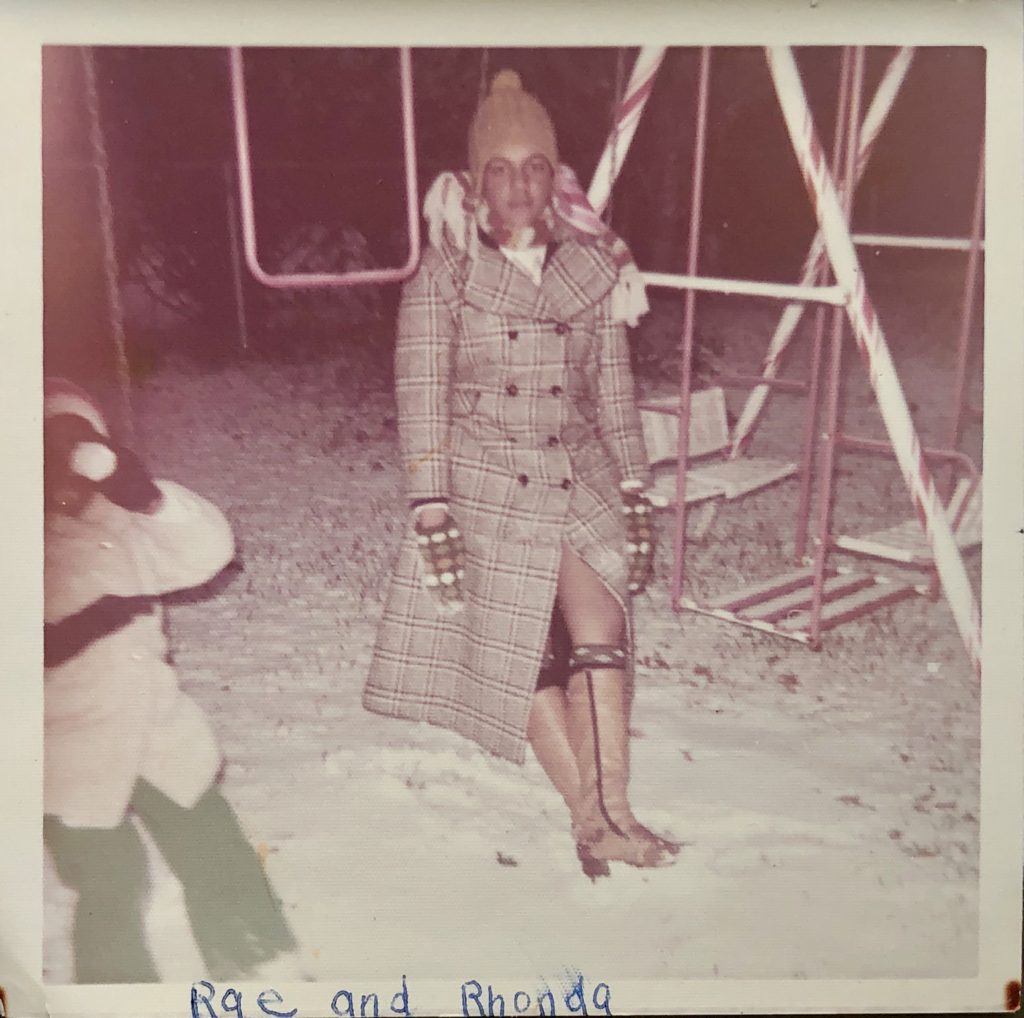

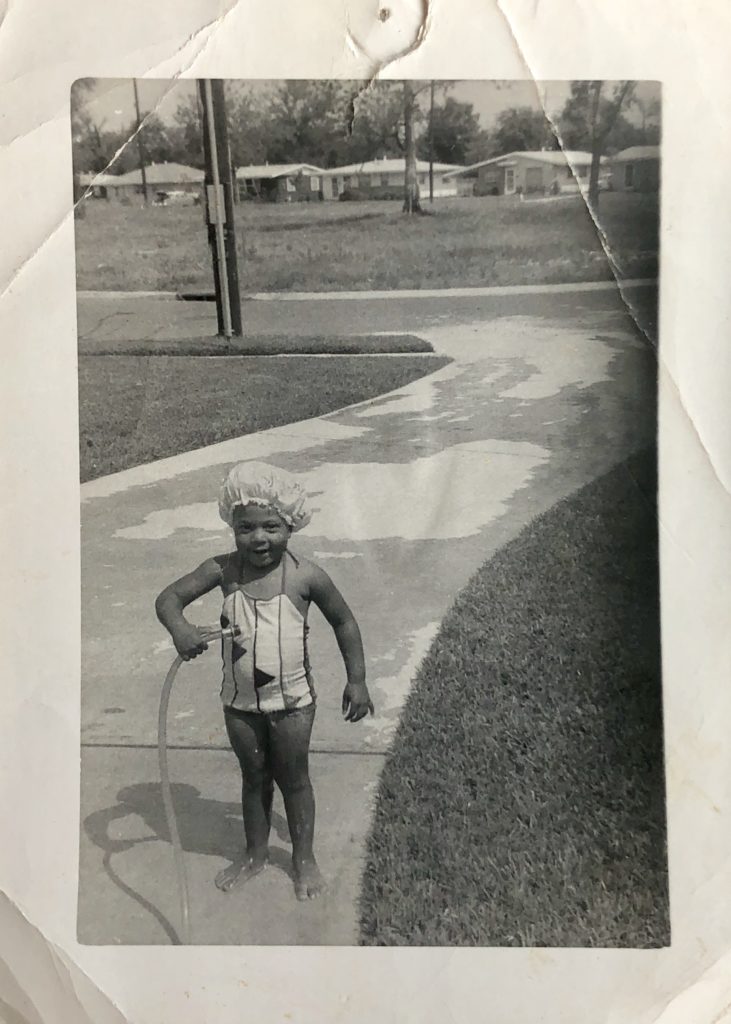

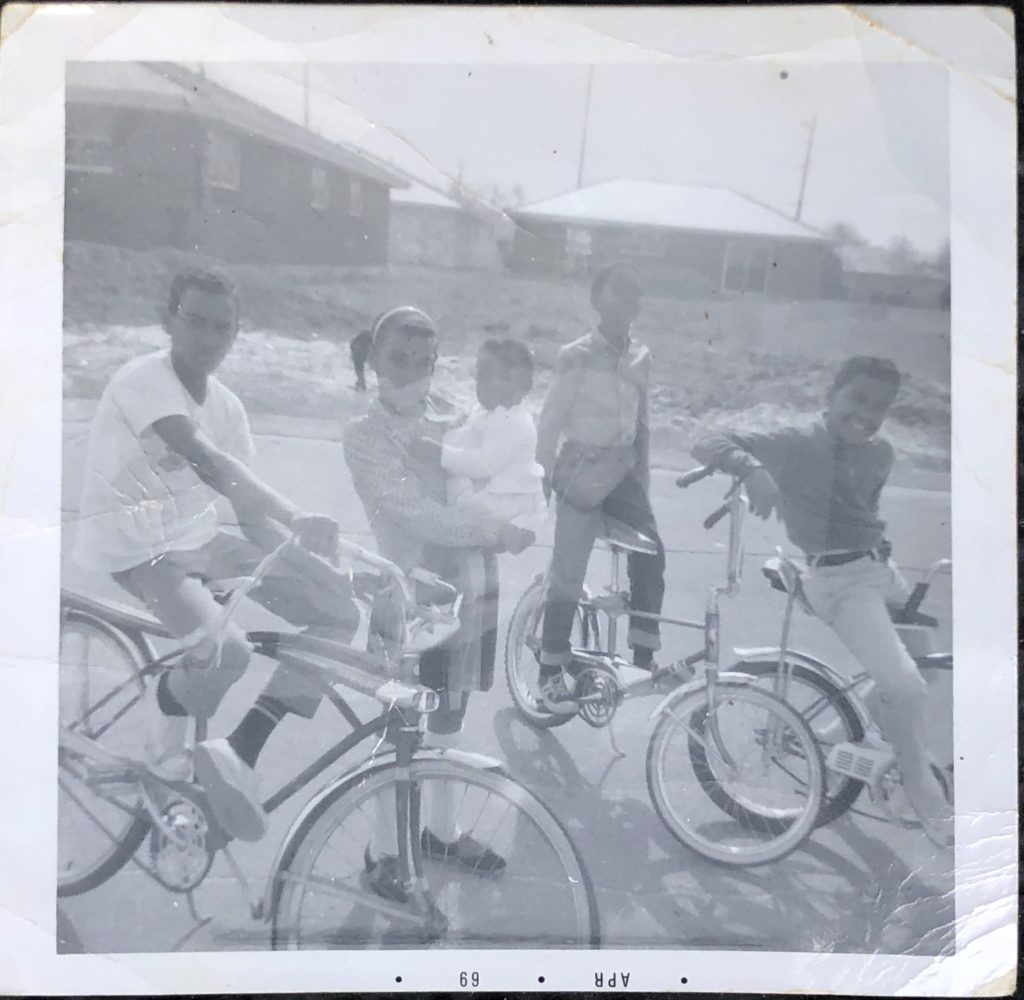

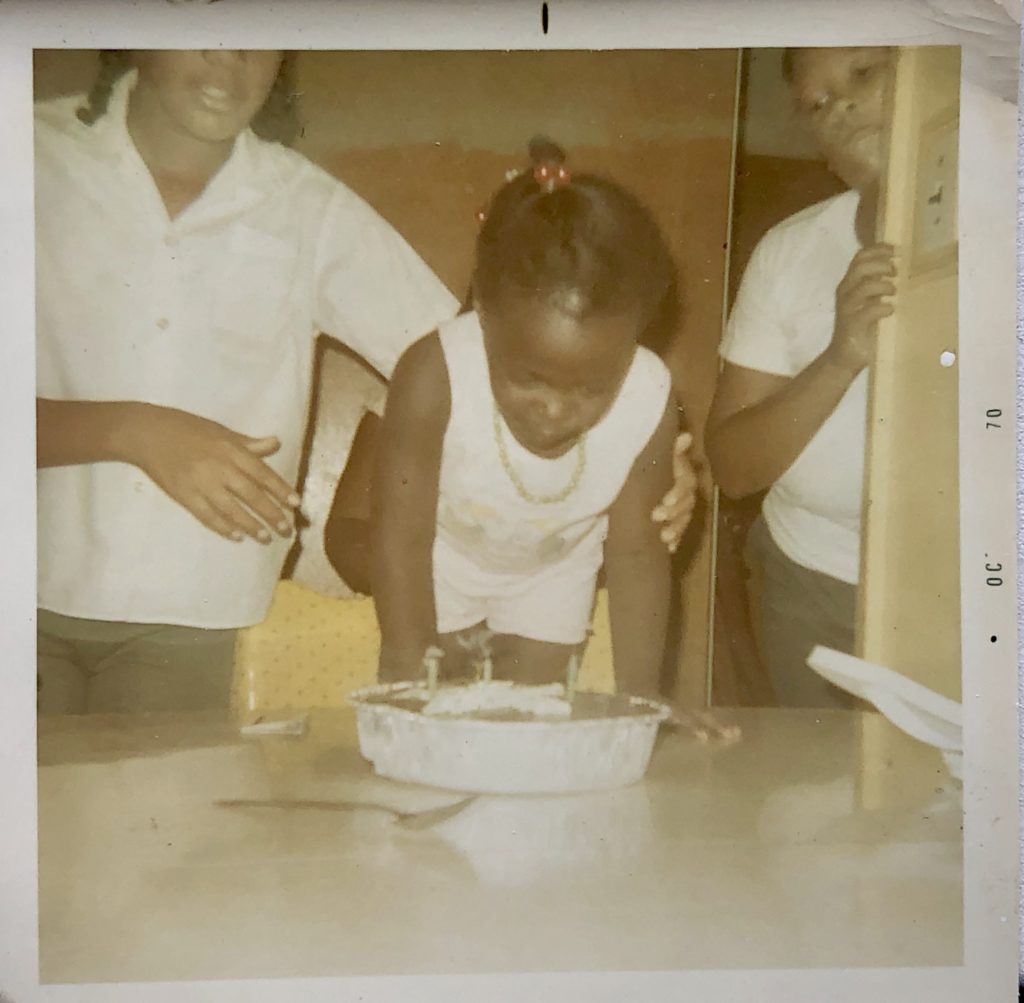

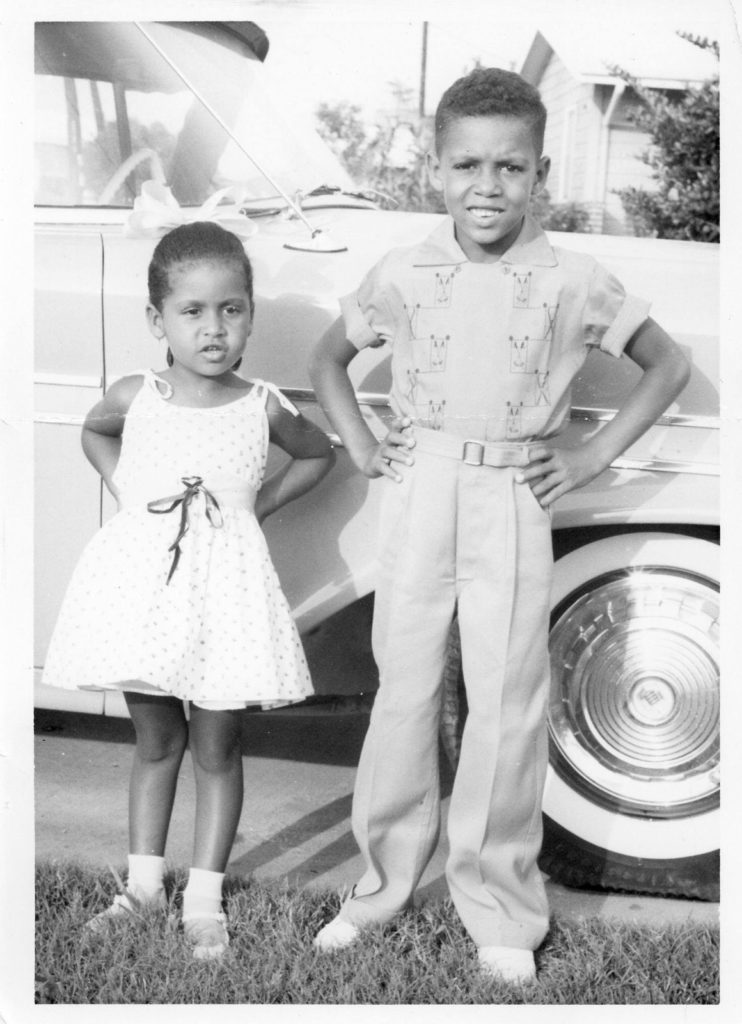

Mayberry Reimagined

Family life in Pontchartrain Park

“Growing up here was like being in Mayberry.”

– Dwight Richards, interviewed by the Preservation Resource Center, July 2019

“In those days, they all helped one another… Mr. Williams was a concrete guy, Mr. Robert was a tile man, Mr. Floyd was another carpenter, and so on. It was very much a barter system.”

– Dwight Richards, interviewed by the Preservation – Lionel Khaton, “The Wonder Years in Pontchartrain Park: a resident remembers growing up in ‘The Park’,” Preservation in Print, June 2019 Center, July 2019

“Our parents felt safe. They felt like it was okay to let us out and to allow us to play… where in our neighborhood before, we could go no further than the porch.”

– Ginger Baptiste Lopez, interviewed by the Preservation Resource Center, July 2019

“For blacks in the 1950s, nowhere else in the nation were they building a subdivision where they had tennis courts, a golf course, a stadium… It was a really wonderful place.”

– Earnestine Bennett-Johnson, interviewed by the Preservation Resouce Center, July 2019.

“Pontchartrain Park Pioneers” oral history project

The “Pontchartrain Park Pioneers” oral history project is presented by the Center for African & African American Studies at Southern University of New Orleans with special thanks to the National Park Service, the U.S. Department of the Interior through the Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism, and the Louisiana Office fo Cultural Development and the Division of Historic Preservation. It has been published here by the Preservation Resource Center of New Orleans with permission.

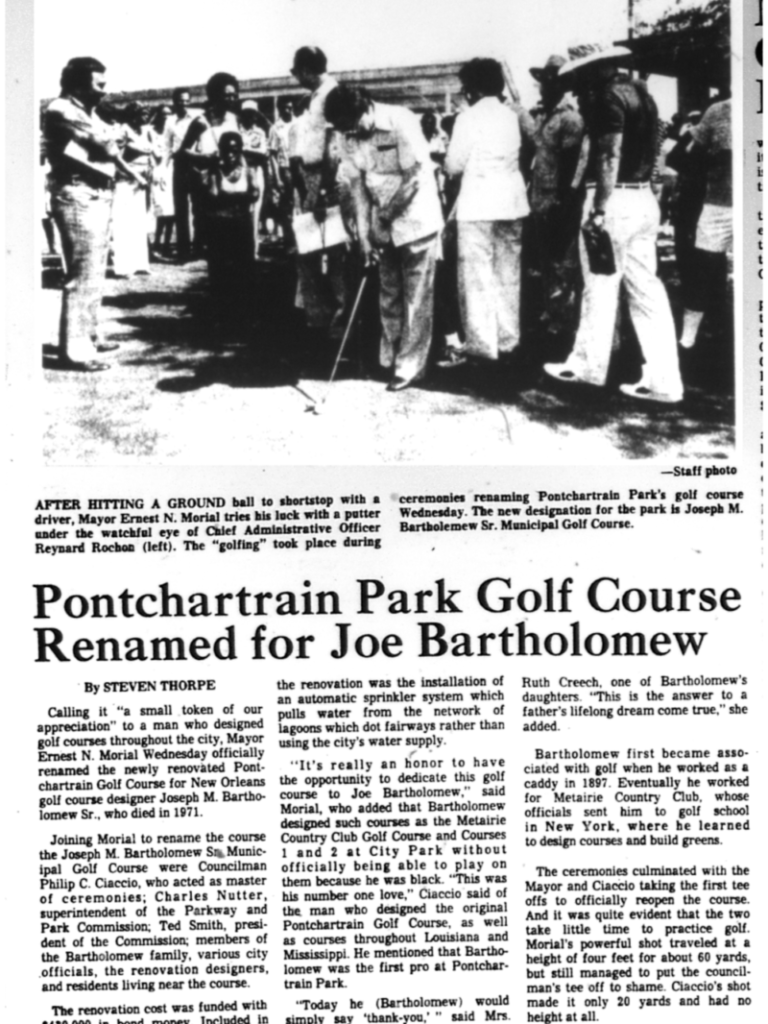

First Tee

When the Pontchartrain Park golf course opened in 1956, it was the only public golf course open to African Americans in New Orleans. Joseph Bartholomew, who designed the 18-hole course, had been a caddy at Audubon Golf Course starting at age 7. He learned about golf course engineering under architect Seth Raynor in Southampton, N.Y. Back in New Orleans, Bartholomew designed the course at Metairie Golf Club and New Orleans’ City Park’s No. 1 and North courses, as well as facilities in Covington, Hammond, Abita Springs, Algiers and Baton Rouge. Due to segregation, the Pontchartrain Park golf course was the first one designed by Bartholomew at which he was allowed to play.

Hurricane Katrina

On Aug. 29, 2005, the levee failures after Hurricane Katrina inundated the neighborhood with more than 15 feet of water in some places, claiming lives and ensuring no structure escaped damage. The neighborhood was previously damaged by Hurricane Betsy in 1965, but the widespread loss of the 2005 flooding was unprecedented.

“Pontchartrain Park may have crumpled under the floodwaters, but it will not wash away from the city’s landscape. It is a very vibrant community. It’s coming back.”

– City Councilwoman Cynthia Hedge Morrell, The Times-Picayune, Oct. 30, 2005

Many residents returned to live in FEMA trailers while struggling to navigate insurance and federal relief programs. Their commitment to remaining in Pontchartrain Park is evident today in hundreds of restored homes. However, numerous houses were demolished, and their lots remain empty 14 years after the storm.

Restoring Pontchartrain Park became a city priority thanks to the tireless work of community members, including Gretchen Bradford, who was honored by the NAACP for her efforts as president of the neighborhood association. Launched in 2007, Gentilly Fest helped raise awareness of The Park’s value as community-wide asset. Wesley Barrow Stadium reopened in 2012 with support from Major League Baseball. The city opened a new clubhouse for the Joseph M. Bartholomew Golf Course in 2014.

In 2019, the Preservation Resource Center partnered with the Pontchartrain Park Neighborhood Association to nominate the neighborhood to the National Register of Historic Places. The historic district was officially added to the National Register in 2020.

“Now, I see young families moving in. Hopefully now they’ll have kids, and a whole generation of kids can grow up in Pontchartrain Park as it is today. It changed its face quite a bit after Katrina, but for the better. Now people came in, new blood. And one of the great things now is that Pontchartrain Park and Gentilly Woods [are] all one community now, and that’s absolutely great … That’s a great sign of the times we live in today. Now, its a community for everybody.”

– Dwight Richards, interviewed by the Preservation Resource Center, July 2019

Notable residents of Pontchartrain Park

- William Roosevelt Adams, MD, pioneering medical doctor and Civil Rights activist.

- Dave Bartholomew, Grammy Award-winning musician, composer, songwriter, bandleader, producer and arranger. He received the Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement and was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

- Terence Blanchard, Grammy Award-winning musician and composer, nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Score in 2019.

- Harold “Duke” Dejan, jazz saxophonist and leader of Dejan’s Olympia Brass Band.

- Nils R. Douglas, Civil Rights attorney and one of the first African-American graduates of Loyola University Law School. He defended members of the Congress of Racial Equality who had been arrested at sit-ins on Canal Street. His firm won a landmark 1963 ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court, successfully overturning the city’s ban on those peaceful protests.

- Lionel Ferbos, renowned jazz trumpeter.

- Henry Hayes, Civil Rights leader and entrepreneur. Hayes owned the Hayes Chicken Shack, a popular venue for social and political events.

- Lisa Jackson, chemical engineer and former administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2009-2013). She was the first African American to lead the EPA.

- Bernette Joshua Johnson, Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court (2013-present)

- Eddie Jordan, first black district attorney of New Orleans (2003-2007) and first African-American U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Louisiana. Jordan successfully prosecuted former Louisiana Gov. Edwin W. Edwards in 2000 for racketeering and fraud.

- Frank Lastie, renowned musician.

- Larry McKinley, radio personality, concert promoter, co-founder of Minit Records and “the Voice of Jazz Fest”

- Ernest “Dutch” Morial, first black mayor of New Orleans (1978-1986).

- Marc Morial, former mayor of New Orleans (1994-2002), current president of the National Urban League and son of Dutch and Sybil Morial

- Sybil Morial, educator, author and wife of Mayor Ernest “Dutch” Morial

- Wendell Pierce, film and television actor, winner of the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Actor in a Television Movie

- Irma Thomas, Grammy Award-winning singer

- Gwen Thompkins, host of Music Inside Out on WWNO Radio, former foreign correspondent for National Public Radio and former senior editor of NPR’s Weekend Edition

- Ernest Wright, Civil Rights activist and labor organizer who established the People’s Defense League. He was the first African-American social worker hired by the

City of New Orleans.

This project made possible thanks to a grant from the Louisiana Division of Historic Preservation.